Preliminary remarks by the authors

We are at the beginning of a new age of wars. Wars between transnational power blocs, wars between existing and nascent nation states and wars against both fleeing and rebellious populations. Wars over strategic resources, wars over food and water, wars over geostrategic power constellations and territorial claims. But no matter what the wars of the present and future may be fought over, we firmly refuse to join any party in them, as every war is directed exclusively against the exploited and oppressed of this world and only benefits the powerful in increasing their wealth and their domination over life. However, it cannot follow from this that we will passively watch as the rulers prepare the slaughter, commit genocides and massacres and bring destruction and misery upon people and life itself. While it is clear that we will never turn our guns on each other at the command of the MASTERS, nothing in the world will prevent us from fighting with our own weapons against the mere facilitation of war, against nationalist propaganda, the military-industrial process of progressive genocide, and not least the very infrastructure of war.

And it is precisely this infrastructure of war, or today’s modern “dual use” infrastructure of the “peaceful” exploitation and military destruction of people and nature, that we want to focus on in this article. We’ll use the example of the so-called Scan–Med corridor (Scandinavian-Mediterranean corridor), one of the EU’s most important infrastructure transport axes, as well as some of its current sub-projects for expansion and constructive reinforcement. In doing so, our aim is not to yet again demonstrate that the fight against war always includes the fight against the “peaceful”, i.e. frictionless exploitation and destruction, against the industrial and colonial project, but rather to make a small contribution to pointing out concrete points of attack in this fight. At the same time, we encourage people to carry out their own analyses of the military-industrial complex, its raw materials and its logistics, with nothing less in mind than its efficient sabotage. We feel the lack of such an analysis all the more sharply because we are of the opinion that our ability to fight domination (and its wars) is irrevocably dependent on knowing its infrastructures, understanding the mechanisms that make them function and, not least of all, possessing the necessary skills as well as a certain routine for attacking it at identified weak points.

The Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T)

The Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T) is a network of roads, railways, airports and waterways planned by the EU within its member states. Its goal is to ensure the fast and smooth transportation of goods, raw materials, and energy carriers across national borders, in addition to military equipment, supplies, and troops, though the latter are often only mentioned in strategy papers.

It consists of a core network, which in turn is comprised of nine “multimodal” core network corridors stretched across the entire territory of the EU. These corridors connect, for example, the North Sea region with the Mediterranean region, the Baltic Sea with the Adriatic, the Mediterranean metropolises in a east-west direction, running along the Rhine and Danube river, or the Atlantic coast. They are multimodal, which means that they at minimum consist of road and rail routes (and often also waterways, at least partially), and that they connect airports and seaports by land. In other words, if one mode of transport fails or is delayed, it should be possible to replace it simply and easily with a parallel transport route along the same transport axis.

It is no coincidence that this redundancy of transport routes, this “multimodality”, is a requirement for military transport axes used for the movement of troops and their equipment and supplies, as is the compatibility with axle loads over 22.5 tons on around 94% of the route. After all, this military useability was taken into account by the EU and its member states from the outset.

The Scan–Med corridor

The Scan–Med corridor (i.e. the transport corridor connecting the Scandinavian countries with the Mediterranean) is the longest of the TEN-T core network corridors and runs from Oslo and Helsinki via Rostock – Berlin – Leipzig / Hamburg – Bremen – Hanover, Nuremberg – Munich – Innsbruck (Brenner) – Verona – Bologna – Florence – Rome – Naples – Palermo to Malta. It crosses the North Sea–Baltic Corridor in Bremen, Hanover, Berlin and Hamburg, the Mediterranean Corridor in Verona, and the Rhine–Danube Corridor in Munich and Regensburg. It also connects the seaports of Hamburg, Gothenburg, Bremen, Rostock and the airports of Munich, Berlin, Leipzig and Hamburg via transport routes on land. Around 1100 freight trains leave the port of Hamburg every week for inland destinations along the Scan–Med corridor. In the other direction, this corridor connects most of the larger and medium-sized Mediterranean ports in Italy via the Brenner Pass especially with Germany. This allows time savings of several days when transporting goods from or to the so-called Far East, if they can be handled by land instead of taking the sea route via the port of Hamburg.

What applies to “civilian” goods also applies to military goods and troops thanks to the “dual-use” strategy in the domain of infrastructure. The Scan–Med corridor not only connects the North Sea naval bases of the German Armed Forces with the Mediterranean ports of Italy, but also makes it possible to balance troop and material movements via some of the west-east axes. For example, we still clearly remember how US military equipment that landed in ports such as Palermo or Bremerhaven as part of the NATO exercise “Defender 2020” took precisely these routes to the US bases, especially in Germany, from where it would have left for Poland if the exercise had not been canceled. From a military point of view, the Scan–Med corridor is also indispensable with regard to the German arms industry and its supply of raw materials and semi-finished products, both in “peacetime” and in the event of war. The arms industry based in the Munich/Ingolstadt/Augsburg metropolitan region in particular, as well as the Bavarian chemical triangle near Burghausen/Burgkirchen/Trostberg/Waldkraiburg, which is important for the arms and oil supply of southern Germany, mainly handle their logistics along this corridor “out of necessity” (as there is no easy alternative) .

Current bottlenecks and corresponding expansion projects

The two most important bottlenecks in the Scan–Med corridor are currently at the Brenner Pass and the Fehmarn Belt, and they affect rail traffic in particular. At the so-called Fehmarn Belt strait, motor vehicles and trains travel on the so-called “Vogelfluglinie”, the most direct connection between the cities of Copenhagen and Hamburg, an approximately 19-kilometer route between the German island of Fehmarn and the Danish island of Lolland so far via a ferry line. The Fehmarn Belt Tunnel, which is to be built as a road and rail tunnel with 4 tubes for traffic, as well as a rescue and maintenance tube by 2029, is intended to upgrade this section of the route in the future and thus eliminate the bottleneck caused by the ferry service. At the same time, the Fehmarnsund Bridge, which connects the German mainland and Fehmarn, is to be replaced by another sea tunnel, the Fehmarnsund Tunnel, which is to be built at the same time to accommodate the growing volume of traffic and in particular the 835-metre-long freight trains that will then run there.

The second major bottleneck of the Scan–Med corridor is in the Alps, more precisely at the Brenner Pass. On one of the most important Alpine crossing routes in Europe, rail transport in particular, especially freight, poses such a major challenge due to the steep gradients of the route that it is often more economical to transport goods by truck. The Brenner Base Tunnel, which is due to be completed by 2032, aims to change this. In order to guarantee a stable connection, new access routes are also being built or expanded both in the north (Austria and Germany) and in the south (Italy) to allow capacities of several hundred trains per day.

In addition, there are numerous smaller bottlenecks and expansion stages on sections of the Scan–Med corridor which do not comply with the EU’s requirements for the core network corridors,some of these within Germany should be singled out as examples. In rail transport, for example, the northern approach route of the Brenner Base Tunnel is so far lacking (which is to be newly built between Grafing and Rosenheim), as well as the planned and building bypass routes between Hanover and Hamburg (as part of the Optimized Alpha E + Bremen), and the extension of existing local routes. The railroad line between Hof and Regensburg, which is part of Deutsche Bahn’s so-called Eastern Corridor, has not yet been electrified. A new Munich-Ingolstadt line with a connection to the Munich airport is also included in the specifications for the Scan–Med corridor to be completed by 2030. Numerous transshipment stations also do not currently meet the required standards, particularly with regard to freight trains longer than 740 meters, including among others Munich, Nuremberg, Hanover, Rostock, Lübeck, Großbeeren, Schkopau and Hamburg-Billwerder.

Requirements for the military useability of the corridor

In order for the transport axes, which were primarily built for civilian purposes, to actually be used for military purposes in the sense of a “dual use” strategy, a number of requirements must be met, such as those defined in the European “Action Plan on Military Mobility”. These include, for example, capacity for axle loads of 22.5 tons, as well as the multimodality of the corridors, i.e. the ability to switch, more or less at any moment, from road to rail or waterway and vice versa, should one of the parallel infrastructures be seriously damaged. In addition to parallel transport routes of various types, these are primarily transshipment stations and ports that can transfer goods from road to rail and vice versa, or from ship to road/rail. Such transshipment stations, referred to as “Rail-Road Terminals” within this EU infrastructure project, are located along the Scan–Med corridor in a south-north direction within Germany in Munich, Nuremberg, Hanover, Berlin, Bremen, Bremerhaven, Hamburg, Lübeck and Rostock.

In addition, a sufficient supply of fuel along the transport corridors is essential for their military useability. This is because the transportation of troops and military equipment consumes a huge amount of energy, which cannot simply be conjured up. Countless filling stations for cars, trucks, trains, planes and ships are needed to supply the civilian transportation system, which is accomplished on a daily basis using sophisticated logistics consisting of pipelines, freight trains and tank trucks. Roughly speaking, the fuel produced in the refineries (where crude oil usually arrives via pipeline, see below) is transported via pipelines, tankers and tank wagons to so-called oil depots, from where it is also transported via tank wagon or truck to the various filling stations, as well as to smaller and more distant oil depots.

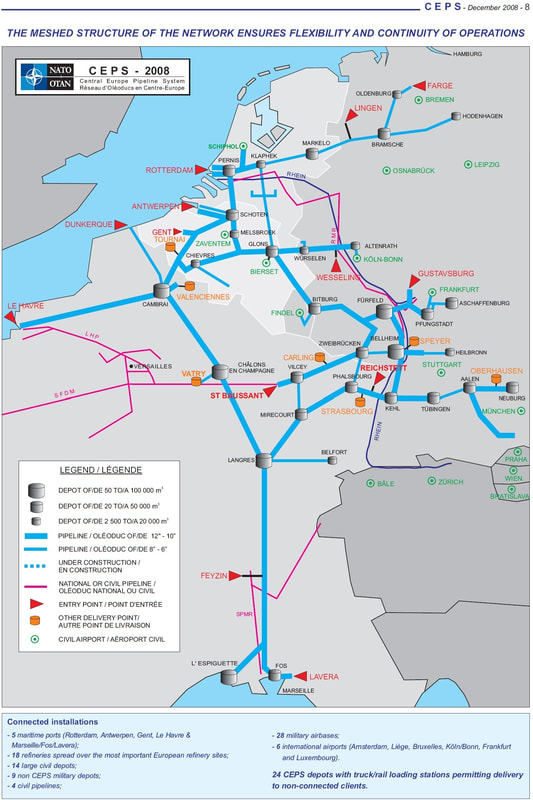

Some strategically important oil depots for the military in Germany and throughout Europe are connected by a NATO pipeline network, which today is sometimes also operated by civilian operators, but ensures military priority use if necessary. There are a total of 12 active oil refinery sites in Germany, located in Burghausen, Brunsbüttel, Gelsenkirchen, Hamburg-Haburg, Hemmingstedt (Heide), Ingolstadt, Karlsruhe, Cologne, Leuna, Lingen (Ems), Schwedt (Oder) and Neustadt / Vohburg. They are supplied via four central pipeline systems:

- The Nord-West Ölleitung (North-West oil pipeline) and the Norddeutschen Ölleitung

(North German oil pipeline), which together supply the refineries in Lingen, Cologne, Gelsenkirchen and Hamburg-Harburg with crude oil via the Wilhelmshaven oil port. - The South European pipeline, which supplies the refinery in Karlsruhe from the port of Marseille and is additionally connected to the Transalpine pipeline (TAL), which in turn pumps oil from the port of Trieste to Burghausen, Ingolstadt, Karlsruhe and Neustadt/Vohburg, in parallel to the Danube.

- A pipeline from Rostock to Schwedt and from there to Lingen, which has reached its capacity limits (particularly since the boycott of Russian oil, which previously also arrived in Schwedt via the Druzhba oil pipeline) and is to be upgraded and expanded at a cost of 400 million euros.

From the refineries, the fuel takes a mostly opaque and constantly rescheduled route via pipelines, tank wagons and trucks to the appropriate oil depot or directly to the various filling stations.

However, NATO’s Central European Pipeline System (CEPS) is more likely to be used for the primary military fuel supply anyway. It has military sites in Lauchheim-Röttingen (Aalen), Altenrath, Mainhausen (Aschaffenburg), Bellheim, Niederstedem (Bitburg), Boxberg, Bramsche, Wonsheim (Fürfeld), Hademstorf (Hodenhagen), Hohn-Bollbrüg, Untergrupppenbach-Obergruppenbach (Heilbronn), Huttenheim, Kork (Kehl), Weichering (Neuburg an der Donau), Littel (Oldenburg), Pfungstadt, Bodelshausen, Würselen and Walshausen (Zweibrücken), as well as civilian facilities in Ginsheim-Gustavsburg, Honau, Krailing (Unterpfaffenhofen), Oberhausen (Neuburg an der Donau) and Speyer, and includes a total of 24 oil depots in Germany alone, each with an estimated fuel capacity of between 20,000 and 100,000 cubic meters. The refineries in Wesseling (Cologne) and Lingen (Emsland) as well as the Gustavsburg oil depot, which is strategically and conveniently located at a rail junction on the Rhine and even has its own port, serve as entry points for fuel supplies into Germany. In addition, numerous other oil depots with connections to the CEPS have rail links and can therefore be converted into entry points. Finally, there are the North Sea and Mediterranean ports, as well as the numerous oil depots in Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and France, and the refineries connected to them, to compensate for any possible fuel shortages.

However, this is also desperately needed, as the fuel requirements of an army on the move are almost immeasurable. A tank, for example, consumes at least around 150 liters of diesel per hour of operation (large battle tanks can also consume a good 600 liters!), while a fighter jet can quickly consume between 5,000 and 10,000 liters of kerosene per hour of operation. Of course, you can count the days on one hand until the fuel reserves in the military oil depots are used up. For the Scan–Med axis in particular, it is worth noting that the part of the route between the greater Munich-Ingolstadt area and Bremen/Hanover is relatively far removed from the CEPS military pipeline network, which is essential for Germany. This means that either other intersecting feeder corridors must be used in this area, which operate via road and rail, or that the military would have to make greater use of civilian fuel supplies. Incidentally, the companies operating the CEPS on German soil are the Fernleitungs-Betriebsgesellschaft (FBG), while the tank wagons required for rail transportation were once handed over to VTG. Moreover, some of the oil depots are currently managed by TanQuid.

In the future, the new hydrogen pipelines slotted to be built and the infrastructures that are being created around hydrogen as an emerging energy source, which are being pushed with great vigor by the green war party in particular, will become increasingly important for supplying the military with fuel. These will presumably initially supply the refineries that continue to supply fuels, but in the longer term, fuel conversions to hydrogen-powered engines are certainly to be expected. At the very least, the planned hydrogen core network intends to extend to up all regions along the Scan–Med corridor.

Translated from Sozialer Zorn